Tiny Colington Island: Big on Historical Firsts

By Ed Beckley

Plopped like black-pepper flecks on the west side of the Outer Banks, the Colington Islands rest in protection from the Atlantic Ocean in the Roanoke Sound. Though historians wrangle, some believe this is where the original English colonists first landed and named the entire land Virginia.

Just over five square miles, Colington has been home to many significant historic “firsts” and has had many incarnations—not to mention many names—since the days it was inhabited by Native Americans.

Pre-History: An Eden for the Native Americans

At one time attached to Bodie Island, nature separated the land to form an island of its own. Archaeologists say Native Americans first occupied it between 200 and 300 A.D., though relics indicate much earlier visits. Algonkians reportedly stayed through the 14th century, enjoying its lush environment and plentiful fish-filled waters. It was a place of fine sand and peats in the swales, marshes and ponds. Spanish moss thrived in its woodlands. The natives had found an Eden, tucked away from the crushing waves and winds of the nearby sea.

1500s A.D.: English Expedition Takes Possession

Scientists say the island was probably uninhabited at the time of first English contact in 1584, a fact supported by the famous first map of the area by colonist John White.

The first Raleigh expedition led by captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlow sailed north up the coast from the West Indies and were abruptly halted at the place where Hatteras juts far east into the ocean. According to Outer Banks’ renowned historian David Stick, the first navigable inlet they discovered was just a trace north of Roanoke Island. It does not exist today. Maps of the era mark the inlet as Trinety Harbor.

Stick wrote that Amadas and Barlow saw the tranquil waters of the broad sounds through the inlet, and they anchored their ships and went ashore.

“And it was there beside the inlet that they took possession of the new land for England, naming it Virginia, in honor of their virgin queen,” wrote Colonel William Byrd, referring to Colington Island as the scene of this ceremony.

1600s: Charles II Grants the Land to Lord Colleton

Originally, the land was known as Carlyle Island (also later as Carlile Island), apparently for renowned military leader Christopher Carlile, who accompanied Sir Francis Drake to the Outer Banks in 1586. Carlile (originally Carleill) led the vanguard of British troops that overran a Spanish-controlled St. Augustine area fort in Florida. Attacking the king of Spain in the New World and finding him poorly defended was a huge moral victory for England. (The island has been referred to many different ways, including Collington Island, Collingtons Island, and Colington Island, as local residents modernized the name.)

In the mid-1600s, civil war broke out in England. King Charles I was executed, but his son survived in exile. Supporters of the monarchy restored it, and put Charles II on the throne. Ever grateful, the new king lavished gifts on those faithful to the Crown.

In 1663, eight men who contributed to his return received a grant of a vast tract of American land and the ability to lord over it as “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietors.” It originally included all of America from the Albemarle Sound east, west and south, including northern Florida to St. Augustine. It was expanded in 1665 to the north near the present Virginia line. They called the area Carolina, which is a female equivalent of the male name Charles, named after the king’s father Charles I.

The first land grant issued by the Lords Proprietors was to Sir John Colleton of Barbados, who was also one of the elite eight. He was a planter in the West Indies, and land represented wealth to him. The grant stated possession “for the heretofore called Carlyle now Colleton Island.”

By the winter of 1664, Colleton’s agent, Captain John Whittie, established a plantation on Colleton Island. David Stick proclaimed it “the permanent first English settlement on the Outer Banks.” Whittie constructed “a 20-foot dwelling house,” which became one of the earliest “Albemarle houses.” Architects say these houses must have been of very modest proportions, seldom larger than two rooms and a loft, and with brick or wood daubed with clay chimneys. They say the house on Colleton Island may have been one or two rooms, and probably weather boarded.

Colleton’s business partner Peter Carteret took over the plantation a couple years later and attempted to grow tobacco and grapes (in hopes of a winery), and he raised hogs. However, his only appreciable profit was from the sale of oil extracted from dead whales which washed ashore on the Banks. Storms ripped apart the plantation and it failed. Carteret said in 1667 “a great storme or reather haricane…carried away the frame & boards of two howses.” Archaeologists have never found the location of the plantation.

1700s & 1800s: Colington Divides

In 1750, residents divided the island into two parts by excavating a canal. That is when Big Colington and Little Colington Islands were born. In the 1800s, settlements were on the south side of the big island, but shifted to the northern shores by the end of the century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the communities of Colington in the southwest and Eagleton in the northwest grew by commercial fishing, until the industry died.

1900s: Bridges Bring Development

In 1903, the Wright Brothers took flight and teenager Johnny Moore just happened upon it. He became one of five witnesses, and after all the flying was done he was so excited he ran up the beach where he encountered William Tate, to whom he shouted, “They done it, they done it, damned if they ain’t flew.” In 1928, the National Aeronautics Association asked Moore and two other witnesses to help them identify the first flight takeoff spot, to place a granite marker. In the 1950s, Aycock Brown deemed Moore the “best known citizen of Collington Island.”

Until the 1950s, Colington was accessible only by boat. Aycock Brown wrote, “The islanders and some of the Dare politicians who made promises are hoping that before the current road program involving Governor Scott’s farm to market and atomic age routes is over that the sand trails of this island, or the main one, is paved.” Then at last the bridges came about.

In the 1950s, the population was said to be no more than that of a hundred years prior. The community had a one-teacher school with four grades. The Meekins store was the only one on Big Collington (a typical country store selling gun shells and soft drinks). The post office had been discontinued and the postal designation was Kitty Hawk RFD No. 2.

Catching and selling eels was a big business, as was trapping muskrats in the winter. The largemouth bass at certain seasons attracted as many Nags Head vacationers asit did salt water angling.

In 1962, there was a move afoot to rename Colington Island to Colleton Island, which failed.

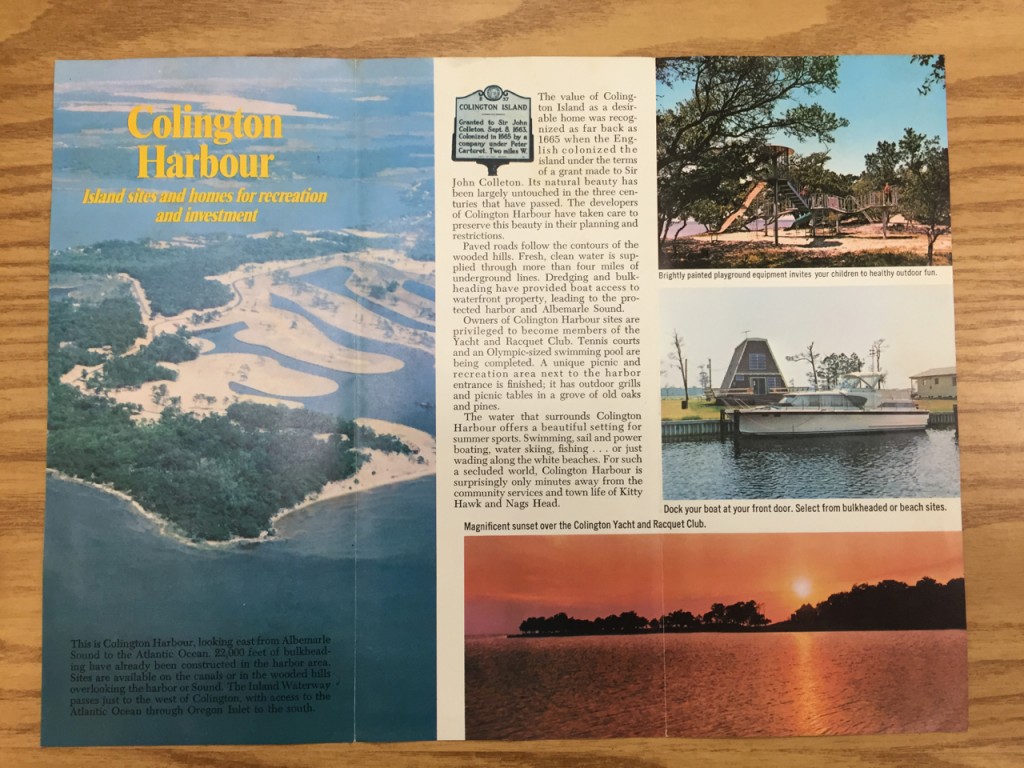

In the ‘60s, David Stick took a small share in the land that would become Colington Harbour in return for helping new owner/developer M.A. Marks with his plan to develop it. Instead, Marks decided to sell it to a group planning an exclusive resort called The Lords Proprietors Colony, which did not get off the ground. The property went to another company that decided to call it Colington Harbour. The initial price for “naturally beautiful beachfront and wooded homesites” was $1,995. Development began in 1968.

1n 1982, resident Murray Bridges became North Carolina’s largest seller of softshell crabs, proudly stating he sold more soft shells than the states of South Carolina, Georgia, Florida and Louisiana combined.

2000s: Colington’s Population Booms

The island has changed in response to nature and culture since its first occupancy, and extremely so in the past few decades. There is no census breakdown, so locals estimate today’s population to be around 6,000. It is considered unimproved property in Atlantic Township of Dare County in District 2.

Colington Harbour is the population center, and has proven very successful after some early bumps with its bulkheads. Homes and buildings ride the topography in the form of seasonal cottages, house trailers, campgrounds, small businesses and an array of new residential subdivisions. Workers commute to and from their homes in droves, so much so that Colington’s State Route 1217 has become one of the busiest secondary roads in North Carolina. For many people, this has become a cause for action.

According to local community organizer Sandy Jett Ball, “The time has come to work for safer and better access to jobs, schools and recreation for pedestrians and cyclists along that road.” Not everyone agrees; however a $17.4 million Department of Transportation improvement project to widen the roads and install a multi-use path is slated to begin in 2018.

Even when zooming in on the map of the Colington islands, it is clear this is a tiny place. And today, more than ever, it is still a desirable environment where people choose to live. Governor Scott’s atomic age vision to expand North Carolina’s network of roads made it easy to get here, there and everywhere, and Colington Islands’ history is taking yet another new turn.