Re-Discovering the Monument to a Century of Flight

By Laura Martier –

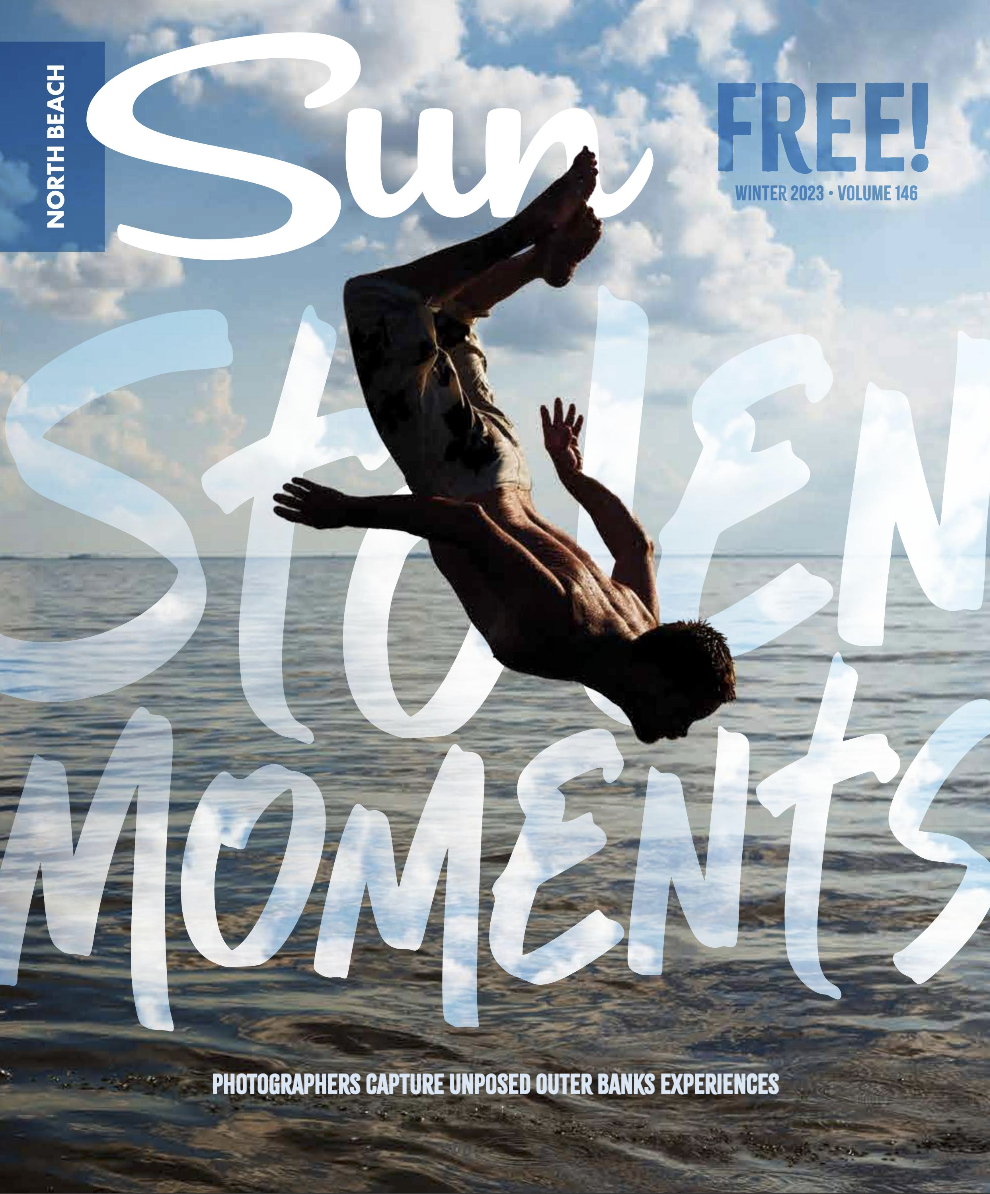

Icarus Monument to a century of flight. Kitty Hawk, NC behind the Aycock Brown Visitor’s Center. Photo by Kati Wilkins.

The Monument to a Century of Flight is tucked away behind the Aycock Brown Welcome Center in Kitty Hawk. Created for the 2003 Centennial Celebration this amazing art collaboration goes largely unnoticed by residents and visitors.

“Humankind is a continuum of pioneers sharing timeless dreams and the boundless possibilities of vast unexplored worlds”

These words are included in a work of local public art commemorating 100 years of flight. Unlike the Wright Memorial, the Monument to a Century of Flight is tucked away behind the Aycock Brown Welcome Center in Kitty Hawk. Created for the 2003 Centennial Celebration this amazing art collaboration goes largely unnoticed by residents and visitors. Most people I question are not aware of its existence.

It is a remarkable place—a sanctity of space that is created when artists and dreamers, government and grassroots, community and commerce unite to actively encourage the creation of public art.

All last summer I made a game of exploring and finding new trails in the forests of live oak and cypress blanketing my Southern Shores neighborhood. My heart always skipped a beat when discovering something hidden and new in such familiar territory. But when I took to the streets, it was a challenge to feel inspired. I had to go out of my way to find even the subtlest spark; garage door and storefront murals, funky house signs, yard art or anything else reflecting the creativity of a community.

With public art on my mind, I decided to revisit this hidden artistic commemoration, ponder public art and reacquaint myself with, what is in my opinion, one of the most impressive public art collaborations in our community.

I pulled into the Aycock Brown Welcome Center and drove around to the south side of the parking lot where an additional parking area appeared to my right. I parked my jeep and walked toward the entrance to the monument. As I approached the sun was halfway to the horizon sending light that reflected off of the face of what looked like a tall and slender obelisk.

A wide, gently inclining concrete path flanked with sturdy steel hand rails led to the site, at first revealing two then three mysterious vertical shapes up ahead until it ended at the base of ten steps. There I could see what appeared to be a circle of fourteen tall metal pylons with half of a globe cast in bronze emerging from the ground in the center of the red brick paved circle.

I sat down on a black granite bench set behind the formation and looked before me.

Hollow brushed steel columns, iridescent in the fading light formed a loose circle; lighting that resembled portholes in the ground had come on, illuminating the structures from below.

Thousands of red brick pavers, 4600 to be exact, are engraved with the names of loved ones, aviators, rotary clubs, businesses and individuals filling the center space.

Each structure has an identical black granite panel affixed to its front that depicts defining moments in aviation history and the men and women who contributed to these accomplishments. It begins with the inaugural flight in 1903 and ends 100 years later with pictures from Mars, the first woman commander of a space shuttle and the International Space Station. Everything in between is included on the fourteen steel sculptures, “ascending in height from 10 feet to 20 feet in an orbit of 120 feet, the distance traveled by the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright in that historic ‘first’ flight.”

“When Orville Wright lifted from the sands of Kitty Hawk at 10:35 on the morning of December 17, 1903 we were on our way to the moon and beyond.” These are the words around the bottom of a bronze casting of the world the metal towers orbit.

Starry, Starry Night swirls etched in the metal surround an abstract rendering of the continents and oceans. The bottom is rimmed with metal likenesses of a variety of aircraft-helicopter, hot air balloon, jet plane, blimp and fighter planes.

I walked out of the center of the circle and stood between two columns, my face toward one and my back to the other. From this view I was looking at a row of aircraft wings, lined up, saluting. They almost looked like they could fold into a formation and take off into the sky, silver wings gliding on air like a steady line of pelicans.

The swirl in the pattern of the brick layout, in the texturing of the metal and also in the bronze seas surrounding the earth reminded me of wind.

I walked the paved path of the perimeter looking at mulched beds of grasses, scrubby pines and native shrubbery opposite the monument. A rabbit crossed my path and turned to look at me before disappearing in a bush. As I descended the shimmering ocean stretched out in the distance before me. I could see a tall, black granite marker at the bottom of the path. Engraved on one side were the names of the artists; Glenn Eure, Hanna Jubran and Jodi Hollnagel Jubran, the architect, Ben Cahoon and Icarus International, Inc. Founded by Glenn Eure, Denver Lindley and Nancy Farnai. On the other the poem “High Flight” written by 19-year-old American pilot, John Magee shortly before his death in WWII.

“High Flight”

John Gillespie Magee

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds, — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of — wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air….

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace.

Where never lark, or even eagle flew —

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

– Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.