Ghost Town: The Forgotten Story of Dare County’s Buffalo City

Written By Amelia Boldaji

Photos Courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center

It’s not something you’ll read in a textbook or see on the big screen, documentary-style — at least, not yet. But the story of Buffalo City, once the largest community in Dare County around the turn of the 19th century, is a colorful one of a mill town and moonshiners that continues to live on. Even now, more than a half a century later, former residents and their descendants still gather every September at the East Lake United Methodist Church for an annual “Homecoming” that celebrates the vanished town just 19 miles west of Manteo.

These collective memories are our lifeline to the past because today Buffalo City is a ghost town. And unlike many other ghost towns spread out across the country, almost nothing visible remains of this once-thriving community — unless, of course, you know what you’re looking for.

Like the physical reality of the now heavily forested area where Buffalo City once stood and prospered, there’s always more to the story than what first appears on the surface.

A Logging Boomtown

The town of Buffalo City sprang up a few decades after the Civil War ended when Buffalo City Mills, a timber and mill company from Buffalo, NY, purchased more than 100,000 acres on the Dare County mainland and set up operations in 1888. The laborers the company brought down south with them, including a number of African Americans and Russian immigrants, were tasked with building a town in the middle of nowhere from the ground up.

Though Buffalo City’s remote location might seem like an odd choice for a major logging operation, it also sat alongside the north bank of Milltail Creek. For those unfamiliar with Milltail, the creek feeds directly into Alligator River, which separates Dare and Tyrell counties and empties into the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway’s Albemarle Sound. This made Buffalo City a prime spot for shipping timber to locations up and down the Eastern Seaboard.

Early on, the mill specialized in harvesting prized juniper wood, which was used to produce shingles that still adorn some of the old oceanfront Nags Head houses. Buffalo City Mills quickly became the biggest logging operation in northeastern North Carolina. Overall, it was a heyday of epic proportions for Buffalo City, resulting in dozens of virtually identical residential houses for company laborers that were built out of scrap lumber. The town also included a hotel, a schoolhouse, and a country store, which was the only place where workers could spend the aluminum, company-manufactured money known as “pluck” in order to meet their basic family needs.

Buffalo City Mills remained in the area for almost two decades before the company decided it had exhausted the premium timber the area had to offer. After that, the large amount of acreage that made up the viable logging area in and around Buffalo City changed hands several times in the coming decades — going first to Dare Lumber Company (when an official attempt was made to change the town’s name to Daresville, though it never stuck), then the three local Duvall brothers (Claude, John, and Ephraim), and finally to the Black Bear Lumber Company. Black Bear Lumber promised to revive and expand the eastern North Carolina timber industry in the 1940s, but soon found that it could no longer make good on that promise, effectively signaling the end of logging in Buffalo City.

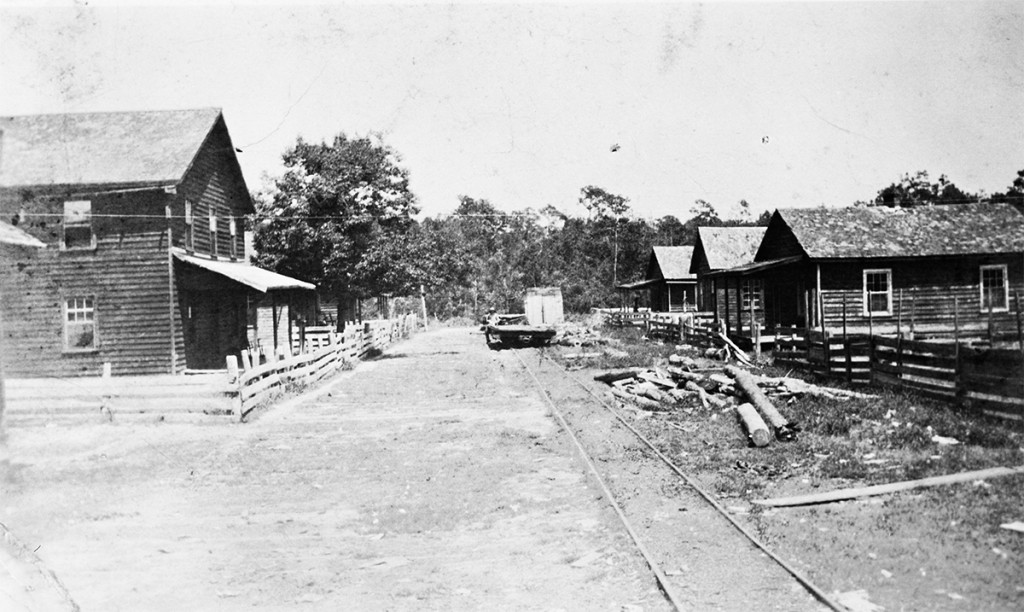

In the midst of this whirlwind, there were several changes to the dynamics of Buffalo City’s logging business — most notably in terms of technology. While timber was originally set afloat down Milltail Creek to the mill, where the logs were then transported on barges, eventually it became more expedient to move the timber to the transport station by train. Historians agree that more than 100 miles of train tracks were laid by hand on the Dare County mainland during the early 1900s, including a track that ran through the middle of downtown Buffalo City and eventually branched off into the woods with extra spur tracks for areas where choice timber was discovered.

Buffalo City had also established its shape by this point: On either side of main street and the central track stood a few rows of red-painted houses for the white residents, while two rows of white-washed houses for African-American and other immigrant residents were erected slightly farther west.

According to many, however, these racial distinctions hardly mattered at the time. Business might have been booming, but even at its peak when a reported 3,000 people lived in the town, life in Buffalo City also meant being able to do without conveniences such as electricity and plumbing. Residents also endured seasonal extremes and wildlife that included virulent insects, alligators and bears — not to mention the soft, swamp-like ground the town and its roads were built on largely by using wood and sawdust from the mill as foundational fillers. There was also no real way in or out of the area except by boat.

In the face of these hardships, Buffalo City’s residents managed to survive by forming an intensely tight-knit community. Together, they looked out for each other, and they also created a moral code all their own.

“There’s no telling how many bodies are buried out there,” says neighboring East Lake native Alvin Ambrose as he describes several ways justice was meted out by community members when they felt the situation warranted it — including whippings and, at least in one instance, the punishment of death by fire. It may not have been the Wild West exactly in Buffalo City, but that frontier spirit was alive and well from beginning to end.

Moonshine Capital of the U.S.A.

Though it’s tempting to think of logging and bootlegging as two distinct industries that operated during different eras of Buffalo City’s history, the truth is that they overlapped. Logging was still a source of income in Buffalo City — albeit a dwindling one as quality timber became increasingly scarce — when residents began producing moonshine in order to make ends meet.

Bootleg liquor has a long tradition in the American South that both pre- and post-dates Prohibition, and this is especially true in North Carolina. Although the 18th Amendment, which banned the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcohol nationwide didn’t go into effect until 1920, North Carolina was the first southern state to pass a referendum banning alcohol 12 years earlier on May 26, 1908. North Carolina was also one of four states that refused to ratify the 21st Amendment ending Prohibition in 1933, and remained a legally dry state until 1937.

Along with many others across the nation, Buffalo City residents soon realized the economic advantages to the underside of Prohibition. With their isolated location, access to natural waterways, and the dense canopy that concealed them from outsiders, Buffalo City turned out to be the ideal spot for lucrative, large-scale bootleg operations.

And large scale was exactly what they went for. Particularly after nationwide Prohibition, it wasn’t long before making moonshine became a virtual community pastime in Buffalo City. It wasn’t your run-of-the-mill homemade whiskey either; this was the good stuff. Though Buffalo City manufacturers made some whiskey with corn, it was their smoother rye version that put them on the map. Known more generally as East Lake whiskey, demand was high for this carefully crafted liquor, particularly in big cities such as Washington, D.C. and New York, where some speakeasies were rumored to have kept specially branded East Lake whiskey cocktails on their menus, while other rival distributors were said to have slapped fake East Lake labels on their bottles in order to improve sales.

Though no exact amounts are recorded, it’s fair to say that massive quantities of the increasingly popular, quality East Lake moonshine were made in Buffalo City over the years. In order to get the liquor over to Norfolk or Elizabeth City for further distribution, the whiskey was often transferred to five-gallon jugs that were sealed with waxed corks and tied onto trotlines that trailed behind boats in the water. If federal revenuers showed up, the lines were cut so that the jugs could sink to the bottom of the creek and be retrieved at a more opportune time.

As all this suggests, there were some risks involved. The sentence for being caught bootlegging then was a year and a day in federal prison, and revenuers were constantly watching the traffic around Buffalo City. The revenuers were at a disadvantage, however, since most of them had to come into the area by water, and local residents not only had highly organized lookouts, but they also sometimes strung thread across the creek. A broken thread meant that revenuers were on their way, which could give moonshiners time to prepare for a raid.

The people of Buffalo City quickly became used to employing a high level of subterfuge. According to one story, the largest shipment of East Lake moonshine actually left the area on August 18, 1937, the night that President Franklin D. Roosevelt attended a showing of The Lost Colony on Roanoke Island to commemorate the 350th anniversary of Virginia Dare’s birth. While most of the available officers were busy with presidential security concerns, Buffalo City bootleggers had planned ahead in order to take advantage of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Prohibition’s federal repeal and the development of airplane surveillance eventually contributed to the decline of moonshine production in the area — but the legacy of Buffalo City’s bootleg past continues to live on. The East Lake Holiness Church was built on moonshine kegs in the 1930s (which the preacher often said was the best way to get the devil under your feet), while the old Dare County administrative building located on Manteo’s Budleigh Street was reportedly funded with moonshine money. East Lake moonshine is even mentioned as being “the best there is” in the 2012 movie Lawless, which was adapted from Matt Bondurant’s acclaimed historical novel about Prohibition, The Wettest County in the World.

“Nobody around here makes moonshine anymore,” says Alvin Ambrose with a sly smile. “Well, not that we know of, of course.”

The End of the Road

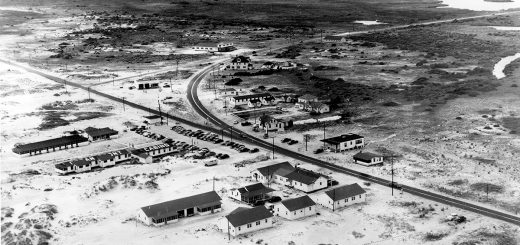

With few remaining job opportunities and the advent of World War II, families slowly began moving away from Buffalo City to areas such as East Lake, Manns Harbor, Elizabeth City, and Norfolk. Eventually there was no one left.

Today, Buffalo City is part of the 152,000-acre Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. If you follow U.S. Highway 64 over the Virginia Dare Memorial Bridge that spans the waterway between Roanoke Island and Manns Harbor, you only have to drive a few more miles before you’ll encounter a small left-hand turnoff for Buffalo City Road — the only real remaining marker for the old town of Buffalo City.

There are few other indicators of the town that time has forgotten, and the now dead-end Buffalo City Road is widely known as “a road to nowhere.” Yet if you venture into the overgrown mass of scrawny pines and gum swamp trees found there, some remnants of Buffalo City and its past inhabitants remain. While this isn’t a trek for the faint of heart as the ground easily gives way underneath your feet and thorny vines attempt to block your progress through the undergrowth, you’ll eventually encounter a number of loose rusting wires, half-buried rail beds, and partial brick structures that are hard to identify. Almost all the old wooden houses and buildings have completely crumbled and rotted away.

“The area’s still deteriorating,” says Cory Hemilright, Manns Harbor native and owner of Manteo’s Bluegrass Island store where he’s created a permanent exhibit that pays tribute to Buffalo City’s past. “At some point it will all be lost.”

In a conversation with Cory and former Buffalo City resident Myra Ambrose, whose family members were the final ones to live in the town, both remark on the fact that many other artifacts must remain out there at the bottom of Milltail Creek and in the swampland that appears to be swallowing the last physical traces of Buffalo City whole. “When you think you’ve heard it all, there are more memories, more pieces of history,” Cory says. It’s a telling statement that speaks volumes about just how much of Buffalo City’s story continues to remain untold — at least, that is, for now.